txt2obj: 3D-Printed DnD Figurines with TRELLIS

We’re summoning gnomes from the ether today ️🔥

I’ll explain how I created this 3D-printed figurine using the new 3D asset generation model TRELLIS, introduced in the paper Structured 3D Latents for Scalable and Versatile 3D Generation (2024).

I’ll start with some technical background, primarily about 3D representations and not the model architecture.1 Skip to the tutorial here.

Part A: TRELLIS in Context

A.0 Image Features with DINOv2

Relevant papers: DINOv2: Learning robust visual features without supervision (2024) and the original DINO Emerging Properties in Self-Supervised Vision Transformers (2021).

The TRELLIS paper makes use of a pretrained DINOv2 encoder to extract image features. Let’s look at that briefly.

DINO is short for knowledge distillation with no labels.2 Using 142 million unlabelled images, DINOv2 trained3 a vision transformer4 model to output image (CLS) and patch tokens representing useful features.5 These features serve as a useful intermediary for tasks such as image segmentation or classification.

The TRELLIS paper uses the patch (not CLS) features provided by a DINOv2 model for both its 3D asset encoding process (turning an existing 3D asset represented in a different way into TRELLIS’s representation format, SLAT) as well as its image-conditional generation process (turning an image prompt into a 3D asset).

I found it helpful to think of image features, and the conceptually similar latents $z_i$ used by TRELLIS, as “semantic colors.” Just like how part of your 2D image or 3D asset can have a color such as “light blue”, representable by the 3-dimensional RGB vector $(180, 220, 250)$, it could also have a feature vaguely corresponding to a semantic category like “ski jacket” or “hydrangea”, representable by an $N$-dimensional feature vector.

A.1 Representations of 3D Assets

Representing a 2D image is usually straightforward. You have an $N \times N$ grid of pixels.6 Each pixel is a tiny square in the grid, described by a color tuple $\textbf{c} = (r, g, b)$, or perhaps $(\textbf{c}, \alpha)$ for a transparency (alpha) channel.

What if you wanted to represent a 3D scene?

You could use a voxel grid. Tiny cubes in an $N \times N \times N$ grid, each similarly described by a color. This works, but since you need $N^3$ voxels, it takes up a lot of memory. Luckily, there are alternatives.

The TRELLIS paper itself uses a new 3D representation called SLAT, explained in A.2. SLAT consists of a “hollow shell” of voxels (much smaller than a full grid) at the surface of a 3D asset, each with a corresponding feature vector that describes its properties.

The TRELLIS paper provides decoders from SLAT to three preexisting representations: 3D gaussians, radiance fields, and meshes.

A.1.1 3D Gaussians

Relevant paper: 3D Gaussian Splatting for Real-Time Radiance Field Rendering (2023).

3D scenes can be represented through a set of gaussians ${ G_i }$, “splats” that fade around the edges. Each gaussian is given by $(\mu, \Sigma, c, \alpha)$: position in space $\mu$, 3D covariance matrix describing the shape of the gaussian $\Sigma$, color $c$, and transparency $\alpha$.

The paper goes into more detail about how 3D gaussian representations can be learned from sparse point clouds and sets of images, and how 2D views can be efficiently rendered from gaussian splats.

TRELLIS decodes each SLAT voxel into $K$ gaussians. Each gaussian is described as $(o, c, s, \alpha, r)$, where the offset $o$ is equivalent to the position $\mu$, and the scales $s$ and rotations $r$ can be thought of as factorizations of the covariance $\Sigma$.

A.1.2 Radiance Fields

Relevant papers: NeRF: Representing Scenes as Neural Radiance Fields for View Synthesis (2020), Strivec: Sparse Tri-Vector Radiance Fields (2023).

NeRF, the original, represents 3D scenes as neural networks. NeRF’s neural radiance field representation is an MLP that map 5D coordinates (3D spatial location $\textbf{x} = (x,y,z)$ and viewing direction $\textbf{d} = (\theta,\phi)$) to a color $\textbf{c} = (r, g, b)$ and volume density $\sigma$.7 The network is structured such that $\sigma$ is predicted only based on $\textbf{x}$.

This MLP can be trained on a set of images of a scene taken from different positions, and be used to generate new 2D views of that scene from arbitrary locations. Loosely, the process is:

- Draw rays (hence “radiance”) from the chosen viewing location in the direction $\textbf{d}$ of each pixel of the desired 2D output

- Sampling some locations $\textbf{x}$ along each ray

- Feed $\textbf{x}, \textbf{d}$ into the MLP

- Using an integral over each ray to estimate the color of the corresponding pixel

It’s actually pretty simple, don’t worry about it.

More directly relevant to TRELLIS are later papers like Strivec. Instead of just an MLP, Strivec uses a field of tensors in 3D space along with a small decoder MLP, keeping the core idea of sampling colors and densities along rays.8 The relevant bit of information about Strivec is that its representation can be written as a set of radiance volumes, each volume corresponding to one SLAT voxel and described by four matrices $(v^x, v^y, v^z, v^c)$.

A.1.3 Meshes

Relevant paper: Flexible Isosurface Extraction for Gradient-Based Mesh Optimization (2023), which introduced the “FlexiCubes” representation of meshes used by TRELLIS.

You can have volumetric meshes, which model the interior of objects, but the meshes TRELLIS is concerned with are the standard polygon meshes you’re probably familiar with from video games.

TRELLIS upscales each SLAT voxel into $4^3 = 64$ smaller voxels. Each smaller voxel is mapped to a vector pair $(\textbf{w}, d)$. $\textbf{w} \in \mathbb{R}^{45}$ are the FlexiCube parameters, which, as the name suggests, allow the voxel to deform so that the final mesh doesn’t look like a bunch of cubes. $d \in \mathbb{R}^8$ is simply the distance each vertex of the voxel to the surface of the mesh.

A.1.4 Non-Exhaustive List of Other 3D Representations

- Point clouds

- Tri-planes

- Signed Distance Functions (SDFs)9

..and more.

A.2 Structured Latent Representation (SLAT)

The TRELLIS paper introduces a new 3D representation called the structured latent representation (SLAT). SLAT represents a 3D asset in an $N \times N \times N$ grid as $z$, where:

\[z = \{(z_i, p_i)\}_{i=1}^{L}, \quad z_i \in \mathbb{R}^{C}, \quad p_i \in \{0,1, \dots, N-1\}^3\]- $p_i$: positional index of an active voxel in a 3D grid that intersects with the surface of the 3D asset $O$

- $z_i$: local latent vector10 attached to the corresponding active voxel $p_i$

- $N$: the spatial length of the 3D grid.

- $L$: the total number of active voxels, $L \ll N^3$

- $C$: the latent dimension

The active voxels $p_i$ form a sparse structure outlining the rough geometry of the object, and the local latent vectors $z_i$ add detailed information about shape and texture. Think of a SLAT representation as a hollow shell whose shape is described by $p_i$, and whose surface is “colored” with features $z_i$.

A.3 Encoding and Decoding SLAT

To encode a 3D asset $O$ to SLAT, whatever $O$’s original representation, the TRELLIS authors follow these steps:

- Get the positional indices of all $L$ active voxels in $O$, ${ p_i}_{i=1}^{L}$. These are the voxel forming the surface of SLAT’s “hollow shell”

- Render images of $O$ from a bunch of randomly chosen viewpoints onto a sphere

- Pass each image into a pretrained DINOv2 model (see A.0)

- Create a 3D feature map using the patch-level features from all images

- Map each voxel $p_i$ onto the feature map and calculate the average $f_i$ of all its corresponding features. This turns $O$ into a voxelized feature $f = {(f_i, p_i)}_{i=1}^{L}$

- Encode $f_i$ to $z_i$ with a sparse VAE11, creating your SLAT $z = {(z_i, p_i)}_{i=1}^{L}$

Remember that TRELLIS also comes with decoders for 3D gaussians, radiance fields, and meshes. Like the encoder, the decoders are also sparse VAEs, and I discussed their outputs a bit more in A.1.

TRELLIS trained the encoder end-to-end with the 3D gaussian decoder to minimize reconstruction loss, then freezed the encoder to train the other two decoders. Training consisted of reconstructing 3D models from 2D views and/or ChatGPT-generated captions.

A.4 Generating Assets with Trellis

Finally, the fun part! TRELLIS generates 3D assets in two stages.12

- Generate the voxel shell (“sparse structure”) ${ p_i }$

- Rather than work with ${ p_i }$ directly, consider a compressed representation $S$

- Convert ${ p_i }$ to a voxel grid $O \in {0, 1}^{N \times N \times N}$

- Compress $O$ with a VAE into $S \in \mathbb{R}^{D\times D\times D\times C_S}$

- Create a noisy $S$, then denoise with a transformer model

- Uncompress $S$ into $O$ and then the desired ${ p_i }$

- Rather than work with ${ p_i }$ directly, consider a compressed representation $S$

- Generate the features ${ z_i }$

- Like with ${ p_i }$, the features are generated via denoising with flow matching, and conditions are injected into cross-attention

Outputs can be edited either by regenerating details ${ z_i }$ only, or by regenerating within a bounding box (3D inpainting).

Part B: DIY 3D-Printed DnD Figurines

Great, TRELLIS can generate 3D assets. Let’s make some figurines!

I decided to generate one of my friend’s characters, a rock gnome named Gimli.

Create Image Prompt (Optional)

TRELLIS accepts both text and image prompts. I recommend using an image prompt, but that’s personal preference. I generated the character with DALLE-3, then removed the background.15 16

Generate GLB with Trellis

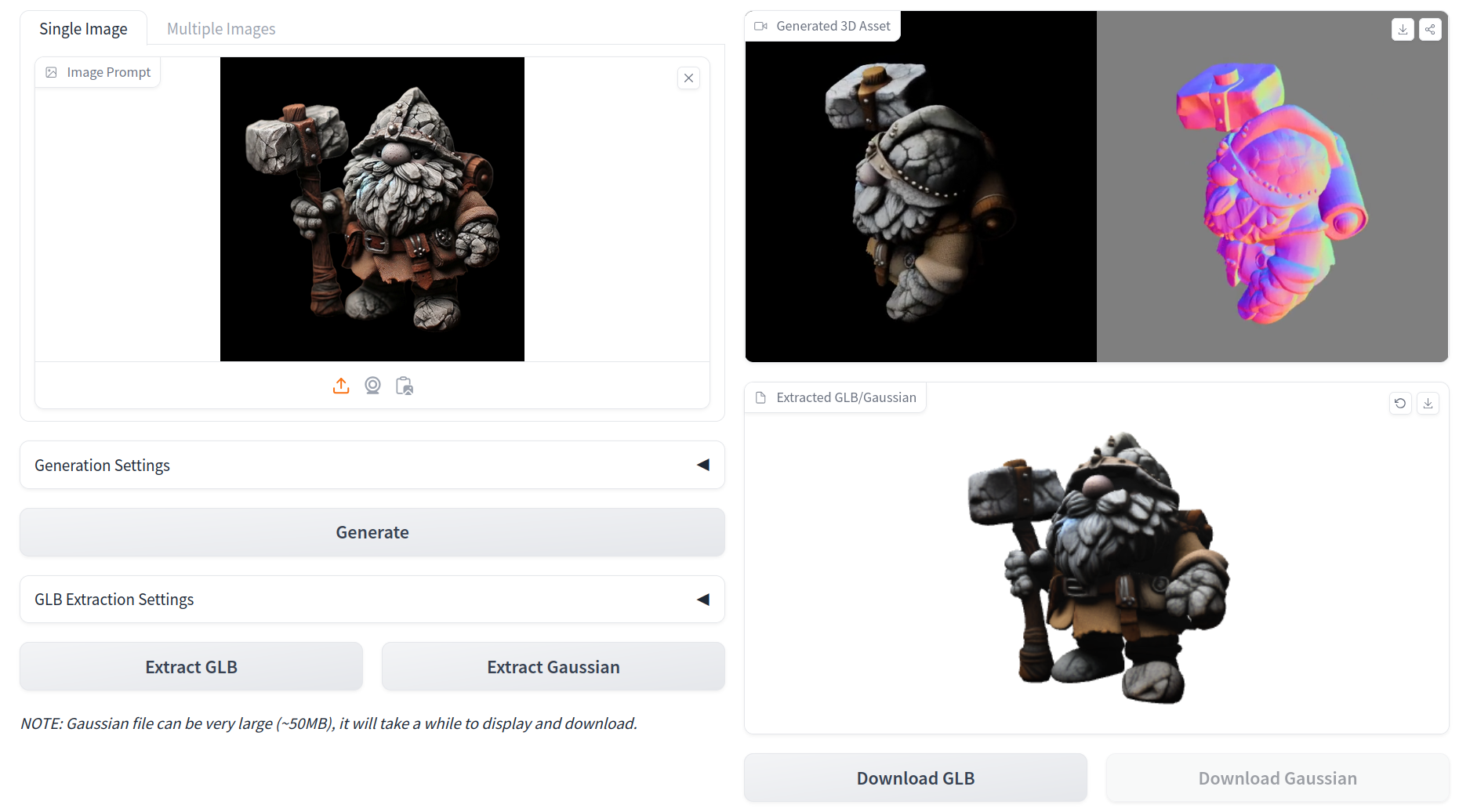

Using TRELLIS (official implementation free on Hugging Face), I generated a GLB file.

Here it is in Blender. At this point, you can edit the file if you want. The TRELLIS paper discusses impainting functionality, but I don’t think it’s available on Hugging Face. I did not edit the file before printing.

Print Your Figurine

I printed two sizes, here they are!

After this, I plan to sand them down and paint them with acryllic. I may post a follow-up after finishing the character designs for the rest of the party.

-

There are already a million articles explaining VAEs, transformers, and conditional flow matching. ↩

-

Acronym abuse in machine learning is not a joke. Millions of families suffer every year. ↩

-

To give an intuitive overview, the training process involved duplicating the model into a “student” and “teacher” fed slightly different transformations of the data. By learning to replicate the output of the “teacher”, the “student” learned robust representations of the images’ features. ↩

-

Fig. 11.8.1 here is a helpful visualization of the patch and CLS representations outputted by a ViT. ↩

-

Vectors, defaulting to dimension

1024for the ViT-L DINOv2 used by TRELLIS. ↩ -

Or $N\times D$ for a rectangle. We’re pretending there’s only one length dimension for simplicity. ↩

-

The density $\sigma$ serves the same function as transparency $\alpha$. ↩

-

I didn’t look into Strivec in detail, but vibes-wise it seems more similar to other popular representations like 3D gaussians or multiscale voxels, with a NeRF flavoring. What made NeRF stand out to me was that it didn’t go for an explicit “small structures embedded in space” approach. ↩

-

Referred to as “implicit fields” by the TRELLIS paper. The “signed” just means positive or negative. ↩

-

According to TRELLIS’s HuggingFace, the dimension of $z_i$

latent_channels=8by default. Given that the dimension of DINOv2 features (and $f_i$) is 1024 by default, 8 is surprisingly small. My intuition for the disparity is that a 2D patch-level feature must be responsible for representing substantially more information than a single 3D voxel’s feature. ↩ -

Variational autoencoder. I won’t be talking too much about model architectures here. ↩

-

Primarily, they use transformers with conditional flow matching, which I talked about in my previous post on TTS models Voicebox, E2, and F5. ↩

-

You better know what CLIP is. Thing’s got a five digit citation count. ↩

-

In the official code, the

SparseStructureFlowModelusesModulatedTransformerCrossBlocks, which perform cross-attentionh = self.cross_attn(h, context)with the condition. ↩ -

Actually, I used a DALLE-3 image generated some months ago from our DnD group chat. It was made through ChatGPT’s interface. ↩

-

I used Adobe’s online background remover. The TRELLIS Hugging Face page says it uses its own background remover, so this may not be necessary. ↩