HiPPO: Explained

A comprehensible guide to the hit framework Recurrent Memory with Optimal Polynomial Projections, also known as HiPPO.

This writeup is primarily based on the paper HiPPO: Recurrent Memory with Optimal Polynomial Projections (2020).

HiPPO describes a method of online function approximation. HiPPO is used in the development of the state space model (SSM) architecture S4, and its sequel Mamba, where HiPPO allows the recurrent model to “remember” past states by efficiently storing an approximation of the entire input signal.

0 Background Knowledge

Basic definitions of key mathematical concepts, alongside explanations of how they come up in the HiPPO papers. Skip to section 1 if you want.

0.1 Orthogonal, Legendre, & Laguerre Polynomials

For more information, see Appendix B.1 of the 2020 HiPPO paper.

A set of orthogonal polynomials ${P_0(x), P_1(x), P_2(x), …}$ satisfies the conditions that the degree of $P_i$ is $i$, and $\int P_i(x) P_j(x) dx = 0$ for all $i \not = j$.

Such sets have useful properties: for example, any polynomial of degree $n$ can be expressed as a linear combination of $P_0(x), P_1(x), …, P_n(x)$, and each $P_k(x)$ is orthogonal to all polynomials with degree $<k$.

Notation-wise, the 2020 HiPPO paper names the following orthogonal polynomials:

- ${P_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$, a sequence of orthogonal polynomials defined with respect to $\mu^{(t)}$

- ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ or ${p_n(t,x)}_{n \in N}$, the normalized version of ${P_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$

- ${g_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$, an orthogonal basis for the approximation function space $\mathcal{G}$, such that $g_n^{(t)}=\lambda_np_n^{(t)}$ for scalars $\lambda_n$1

Orthogonality is defined with respect to a measure, or equivalently the density function of a measure (see 0.3 for background on measures: they are functions that allow you to “weigh” space). Specifically, $\int P_i(x) P_j(x) dx$ is taken with respect to a measure. HiPPO concerns orthogonal polynomials that are defined with respect to different measures $\mu^{(t)}$ at different times $t$, meaning that the polynomials ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ themselves change based on the current time (hence the $^{(t)}$ specification) and on what variation (measure family) of HiPPO is being used.

In the main body of the 2020 HiPPO paper, ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ either refers to the Legendre (for LegT and LegS) polynomials or the Laguerre polynomials (for LagT), though they’ve been slightly modified (scaled, shifted, etc.) from the standard definition to fit HiPPO’s use case.

The standard definition of Legendre polynomials $P_n$ are orthogonal with respect to the density function $\omega^{\text{leg}} = \mathbb{I}_{[-1, 1]}(x)$. The first few $P_n$, as well as a closed-form formula, can be found on Wolfram.2

LegT uses Legendre polynomials modified to be orthogonal with respect to $\frac{1}{\theta} \mathbb{I}_{[t - \theta, t]}(x)$, with $\theta$ being a hyperparameter:

\[\{p_n^{(t)}(x)\}_{n \in N}^{\text{LegT}} = \left( 2n + 1 \right)^{1/2} P_n \left( 2 \frac{x - t}{\theta} + 1 \right)\]LegS, uses polynomials are orthogonal with respect to $\frac{1}{t} \mathbb{I}_{[0, t]}(x)$:

\[\{p_n^{(t)}(x)\}_{n \in N}^{\text{LegS}} = \left( 2n + 1 \right)^{1/2} P_n \left( \frac{2x}{t} - 1 \right)\]LagT is based on the Laguerre polynomials $L_n$3, which are orthogonal with respect to $\omega(x) = e^{-x}$ and supported on $[0, \infty)$. LagT is orthogonal with respect to $e^{x - t}$ and supported on $(-\infty, t)$:

\[\{p_n^{(t)}(x)\}_{n \in N}^{\text{LagT}} = \frac{\Gamma(n + 1)^{\frac{1}{2}}}{\Gamma(n + \alpha + 1)^{\frac{1}{2}}} L_n(t - x)\]with $\Gamma$ being the generalized factorial.

The most important feature of the Legendre and Laguerre polynomials are the measures they’re orthogonal with respect to, as this determines how the memory of the corresponding HiPPO variant works. The details of ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ only come up in the derivations in Appendix D (discussed in 2.4).

0.2 Ordinary Differential Equations and Discretization

For more information, see Appendix B.3 of the 2020 HiPPO paper.

An ordinary differential equation (ODE) takes the form $\frac{dc}{dt} c(t) = f(t,c(t))$. ODEs concern derivatives of a function with respect to a single variable, and do not contain partial derivatives. An ODEs can be discretized for timestep $\Delta t$ by approximating the integral:

\[c(t + \Delta t) − c(t) = \int^{t+ \Delta t}_t f(s, c(s)) ds\]using different methods like forward Euler, backward Euler, bilinear, etc. For example, the forward Euler approximation of the ODE $\frac{d}{dt} c(t) = Ac(t) + Bf(t)$ is:

\[c(t + \Delta t) = \int^{t+ \Delta t}_t Ac(s) + Bf(s) ds \approx (I + \Delta tA)c(t) + \Delta t Bf (t)\]Discretized forms are necessary in most practical use cases.

HiPPO ultimately outputs an coefficient function $c(t)$ that computes the optimal approximation coefficient vector at time $t$. The definition of $c(t)$ itself is important for understanding, but it’s the discretized version of the ODE $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ that would actually be used in an online implementation of HiPPO.

0.3 Hilbert Spaces and Measures

If you’re not familiar with Hibert spaces or measures, don’t worry: they’re formalizations of common, intuitive concepts.

To quote Wolfram4, “A Hilbert space is a vector space $H$ with an inner product $\langle f,g \rangle$ such that the norm defined by $|f|=\sqrt{\langle f,f\rangle}$ turns $H$ into a complete metric space.” The standard Euclidean spaces, $\mathbb{R}^n$ with the vector dot product $\langle v, u \rangle$, are finite-dimensional Hilbert spaces. For example, $\mathbb{R}^2$ has dimension $2$ and contains $v = (1,2), u = (0,3), \langle v, u \rangle = 6$.

HiPPO makes use of an infinite-dimensional Hilbert space, $L^2(\mu^{(t)})$. Informally speaking5, $L^2$ is the set of square integrable functions, $f: X \to \mathbb{C}$ for which $\int_X |f|^2 d\mu$ is finite. $X$ is a measure space: a set, like $\mathbb{R}$ or $\mathbb{C}$, plus some specifications including its measure $\mu$6. Often, $L^2$ is assumed to map from $\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ using the Lebesgue measure $\mu_L$.

A measure a function that maps collections subsets of a space to a “size”, $\Sigma \in X, \mu: \Sigma \to \mathbb{R} \cup {-\infty ,+\infty}$. For example, $\mu_L$ is just your standard understanding of length and area: $\mu_L(5, 3) = 2$.

The $L^2$ norm of $f$ is defined $\Vert f\Vert _{L^2} = \left(\int_X |f|^2 d\mu\right)^{\frac{1}{2}}$ (note that $\langle f,g\rangle = \int_X fg d\mu$ defines the $L^2$ inner product for real functions, so we can also write $\Vert f\Vert _{L^2} = \langle f,f\rangle^{\frac{1}{2}}$). The discrete equivalent is sometimes referred to as the $l^2$ norm and should be familiar: for example, for $x = [3, 4], \Vert x\Vert _2 = (3^2 + 4^2)^{\frac{1}{2}} = 5$.

HiPPO’s $L^2(\mu^{(t)})$ concerns functions $\mathbb{R} \to \mathbb{R}$ using probability measures $\mu^{(t)}$. Probability measures are just measures that satisfy $\mu(X)=1$, since probabilities sum to 1. Crucially for HiPPO’s function approximation and unlike the Lebesque measure, probability measures allow for nonuniform weighing across times, so we can, for example, specify that we “care” more about $[t_n - 10, t_n]$ than $[t_n-20, t_n-10]$ because $\mu^{(t)}(t_n - 10,t_n) > \mu^{(t)}(t_n-20,t_n - 10)$.

The little $^{(t)}$ in $\mu^{(t)}$ refers to the fact that HiPPO uses time-varying measure families. As we’ll see later, HiPPO’s approximation method doesn’t just use one measure, but a different measure for each time $t$, with each measure $\mu^{(t)}$ defined on $(\infty, t]$. The reason should be obvious: we “care about” all past time and don’t “care about” future time, so we want to be able to change our measure as $t$ increases.

By taking the Radon-Nikodym derivative7 of a measure $\mu$ with respect to Lebesgue measure $\mu_L$, we get the density function $\omega^{(t)}(x):=\frac{d\mu^{(t)}}{d\mu_L}(x)$. Throughout the 2020 HiPPO paper, the authors regularly refer to density functions as “measures.” This seems to be standard practice, but it is a little confusing, so watch out.

1 Definitions of HiPPO and the Measure Families

Explaining the definitions of HiPPO and the relevant measure families LegT, LagT, and LegS from the 2020 HiPPO paper.

1.1 Definition of HiPPO

Definition 1 in the 2020 HiPPO paper states:

Given a time-varying measure family $\mu^{(t)}$ supported on $(-\infty, t]$, an $N$-dimensional subspace $\mathcal{G}$ of polynomials, and a continuous function $f: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \to \mathbb{R}$, HiPPO defines a projection operator $\text{proj}_t$ and a coefficient extraction operator $\text{coef}_t$ at every time $t$, with the following properties:

1. $\text{proj}_t$ takes the function $f$ restricted up to time $t$, $f_{\leq t} := f(x) \mid x \leq t$, and maps it to a polynomial $g^{(t)} \in G$ that minimizes the approximation error $\|f_{\leq t} - g^{(t)}\|_{L^2(\mu^{(t)})}$.

2. $\text{coef}_t: G \to \mathbb{R}^N$ maps the polynomial $g^{(t)}$ to the coefficients $c(t) \in \mathbb{R}^N$ of the basis of orthogonal polynomials defined with respect to the measure $\mu^{(t)}$.

The composition $\text{coef} \circ \text{proj}$ is called $\text{hippo}$, which is an operator mapping a function $f: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \to \mathbb{R}$ to the optimal projection coefficients $c: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \to \mathbb{R}^N$, i.e., $(\text{hippo}(f))(t) = \text{coef}_t(\text{proj}_t(f))$.

Let’s go over the definition piece-by-piece:

- Time-varying measure family $\bf{\mu^{(t)}}$ supported on $\bf{(-\infty, t]}$ See 0.3. For each time $t$, we have an individual probability measure $\mu^{(t)}$, a function that maps subsets of $(-\infty, t]$ to nonzero values. This measure determines how much we “care” about segments of past time, and the measure we use itself varies depending on the current time.

- $\bf{N}$-dimensional subspace $\bf{\mathcal{G}}$ of polynomials This is the subspace of all possible functions we could use as an approximation function. $N$ is the size of our approximation.

- Continuous function $\bf{f: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \to \mathbb{R}}$ The function we want to approximate, defined for times $t \geq 0$. When HiPPO is used in S4, $f$ is our entire input signal up to $t$.

- $\bf{\textbf{proj}_t(f_{\leq t}) = g^{(t)}}$ that minimizes $\bf{\|f_{\leq t} - g(t)\|_{L^2(\mu^{(t)})}}$ At each time $t$, we want to find the approximation $g^{(t)}$ that minimizes the squared error, weighted according to $\mu$: \(g^{(t)} := \arg\min_{g \in \mathcal{G}} \\|f_{\leq t} - g\\|_{L^2(\mu^{(t)})} = \arg\min_{g \in \mathcal{G}} \left( \int_{0}^{t} \|f - g^{(t)}\|^2 \, d\mu \right)^{1/2}\)

- $\bf{\textbf{coef}_t(g^{(t)}) = c(t)}$, the coefficients of the basis of orthogonal polynomials defined with respect to $\bf{\mu^{(t)}}$ As described in 0.1 and 0.3, orthogonality can be defined with respect to a measure. The coefficients satisfy $g^{(t)} = \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} c_n(t) g_n^{(t)}$, where the $g_n^{(t)}$ are basis functions of $\mathcal{G}$. These coefficients will be what we actually store in practice.

- $\bf{\textbf{hippo} = \textbf{coef} \circ \textbf{proj}}$ That’s $\text{hippo}$: it maps a continuous function $f: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \to \mathbb{R}$ to the output function $c: \mathbb{R}_{\geq 0} \to \mathbb{R}^N$, which computes optimal approximation coefficient vectors.

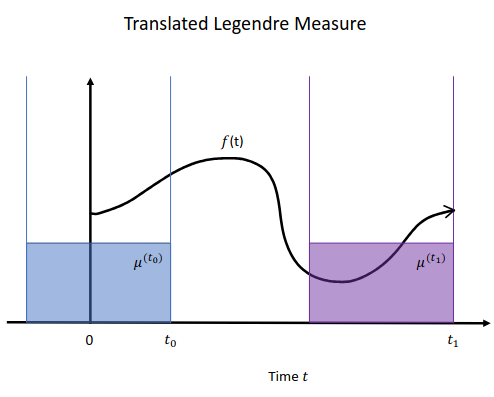

1.2 Definition of LegT (translated Legendre)

Measures in the family LegT take a hyperparameter $\theta$, the “window size”, and are defined:8 \(\mu^{(t)}(x) = \frac{1}{\theta} \mathbb{I}_{[t - \theta, t]}(x)\)

where $\mathbb{I}$ is an indicator function that maps $x \in [t - \theta, t]$ to $1$ and $x \not \in [t - \theta, t]$ to $0$.

The associated output function $c(t)$ is given by the linear time-invariant ODE:

\[\frac{d}{dt}c(t) = -A c(t) + B f(t)\]with $A \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}, \, B \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times 1}$:

\[A_{nk} = \frac{1}{\theta} \begin{cases} (-1)^{n-k}(2n+1), & \text{if } n \geq k \\ 2n+1, & \text{if } n \leq k \end{cases}, \quad B_n = \frac{1}{\theta}(2n+1)(-1)^n\]Neither $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ nor its discretization appear in the definition of HiPPO in 1.1, but as discussed in 0.2, a discretized version of $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ is what would actually be used to update the approximation coefficients $c(t)$ when when HiPPO-LegT is used as an online approximation method. $A$ and $B$ arise from the derivation of $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ from $c(t)$. The “Legendre” part of the name refers to the fact that for HiPPO-LegT, the basis polynomials ${g_n^{(t)}}_{n \in N}$ that $\text{hippo}$ uses are based on Legendre polynomials.

See 0.1 for background on Legendre polynomials, 0.2 for background on ODEs and discretization, and 2.4 for an overview of how the formulas given for $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$, $A$, and $B$ are derived.

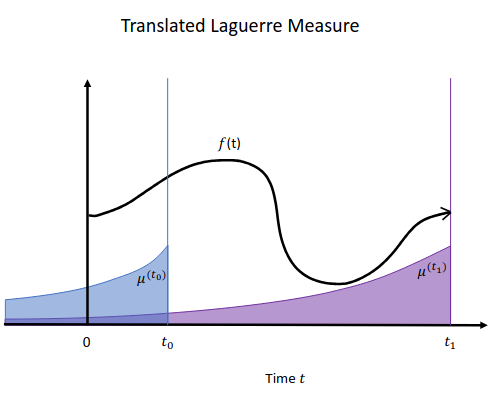

1.3 Definition of LagT (translated Laguerre)

LagT is similar to LegT, but with an exponential decay rather than a window, and is defined9: \(\mu^{(t)}(x) = \begin{cases} e^{x - t}, & \text{if } x \leq t \\ 0, & \text{if } x > t \end{cases}\)

$c(t)$ is given by the linear time-invariant ODE:

\[\frac{d}{dt}c(t) = -A c(t) + B f(t)\]with $A \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}, \, B \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times 1}$:

\[A_{nk} = \begin{cases} 1, & \text{if } n \geq k \\ 0, & \text{if } n < k \end{cases}, \quad B_n = 1\]See 0.1 for background on Laguerre polynomials.

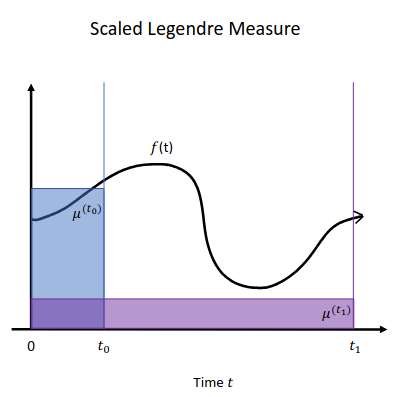

1.4 Definition of LegS (scaled Legendre)

LegS is also similar to LegT, but rather than using a window of size $\theta$, the window size is $t$: \(\mu^{(t)}(x) = \frac{1}{t} \mathbb{I}_{[0, t]}(x)\)

This gives it the slightly more complex ODE:

\(\frac{d}{dt}c(t) = -\frac{1}{t} A c(t) + \frac{1}{t} B f(t)\) with discretized form: \(c_{k+1} = \left(1 - \frac{A}{k}\right)c_k + \frac{1}{k} B f_k\)

with $A \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times N}, \, B \in \mathbb{R}^{N \times 1}$:

\[A_{nk} = \begin{cases} \sqrt{(2n+1)(2k+1)}, & \text{if } n > k \\ n+1, & \text{if } n = k \\ 0, & \text{if } n < k \end{cases}, \quad B_n = 1\]HiPPO-LegS was the most successful variant of HiPPO, and the matrix $A$ above was heavily featured in the S4 paper as “the HiPPO matrix”. In S4, “the HiPPO matrix” was used to initialize and inspire constraints on the parameter matrix $\bf{A}$ of the SSM. This use was inconsistent with how the original HiPPO-LegS was defined, and the authors later laid out exactly what HiPPO was doing in S4 in a follow-up paper. See 3 for links.

2 The HiPPO Framework

How does HiPPO actually work? How do we compute $\text{coef}_t$ and $\text{proj}_t$? Let’s look at more explicit definitions of $\text{hippo}$, then explore how it is computed in practice.10

2.1 The Orthogonal Basis Polynomials ${g_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$

See 0.1.

Central to HiPPO are the polynomials ${g_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$, which form a orthogonal basis of the approximation function space $\mathcal{G}$. The final coefficients outputted by $c(t)$ are coefficients of these polynomials.

$g_n^{(t)}=\lambda_np_n^{(t)}$ for scalars $\lambda_n$, where ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ is a sequence of orthonormal polynomials defined with respect to $\mu^{(t)}$, which in HiPPO were either based on the Legendre or Laguerre polynomials.11 The choice of the sequence ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ indicates what $\mu^{(t)}$ can be used (since orthogonality is a property defined with respect to the measure used), and the algebraic properties of the sequence come up in the derivations of the relevant $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ outlined in 2.4.

2.2 $\bf{\textbf{proj}_t}$ Defined

See equation 19 of C.2 of the 2020 HiPPO paper.

$\text{proj}_t$ maps $f_{\leq t}$ to the polynomial approximation $g^{(t)} \in \mathcal{G}$. $g^{(t)}$ is a linear combination of orthogonal polynomials $g_n^{(t)}$. We can sum the contribution of each $g_n^{(t)}$:

\[f_{\leq t} \approx g^{(t)} := \sum_{n=0}^{N-1}\langle f_{\leq t}, g_n^{(t)} \rangle _{\mu^{(t)}} \frac{g_n^{(t)}}{\Vert g_n^{(t)}\Vert ^2_{\mu^{(t)}}}\](If you need an explanation: the inner product $\langle f_{\leq t}, g_n^{(t)} \rangle_{\mu^{(t)}}$ projects $f_{\leq t}$ onto $g_n^{(t)}$, the squared norm $\Vert g_n^{(t)}\Vert ^2_{\mu^{(t)}}$ is the projection coefficient, and $g_n^{(t)}$ is of course the function itself).

Since $g_n^{(t)}=\lambda_np_n^{(t)}$, $\Vert g_n^{(t)}\Vert ^2_{\mu^{(t)}} = \lambda_n^2$, and so we have:

\[\text{proj}_t := \sum_{n=0}^{N-1} \lambda_n^{-1} \langle f_{\leq t}, g_n^{(t)} \rangle _{\mu^{(t)}}p_n^{(t)}\]2.3 $\bf{\textbf{coef}_t}$ Defined

See equation 18 of C.2 of the 2020 HiPPO paper.

Definition 1 of HiPPO describes the operator as a two-step process, $\text{hippo} = \text{coef} \circ \text{proj}$, where $\text{proj}_t$ computes $g^{(t)}$ from $f_{\leq t}$, and then $\text{coef}_t$ gets the coefficients $(c_n(t))_{n \in N}$ from $g^{(t)}$. This is a useful way to think about HiPPO, but when it comes down to the math, we don’t need to explicitly express $\text{coef}_t$ in terms of $g^{(t)}$.

Recall the output function $c$ maps time to coefficient vectors $(c_n)_{n \in [N]}$ which approximate $f$ as a linear combination of basis polynomials $g_n^{(t)}$. Thus, at time $t$, we can calculate an individual coefficient $c_n(t)$ by projecting $f$ onto the relevant $g_n^{(t)}$:

\(c_n(t) = \langle f_{\leq t}, g_n^{(t)} \rangle _{\mu^{(t)}}\) \(= \int f(x)g_n^{(t)}d\mu^{(t)}\) \(= \lambda_n \int fp_n^{(t)}d\mu^{(t)}\)

We can use the density function $\omega^{(t)}(x):=\frac{d\mu^{(t)}}{d\mu_L}(x)$ (see 0.3) to perform a change of variables:

\[=\lambda_n \int fp_n^{(t)}\omega^{(t)}dx\]Since $\text{coef}_t(g(t)) = c(t) = (c_n(t))_{n\in[N]}$, we get the definition:

\[\text{coef}_t := \left(\lambda_n \int fp_n^{(t)}\omega^{(t)}dx\right)_{n\in[N]}\]Because of what I explained in the beginning of the section, this definition of $\text{coef}_t$ is also a definition of $(\text{hippo}(f))(t)$ itself.

2.4 Calculating HiPPO Coefficients with ODEs

See Appendix C.3 and C.4 of the 2020 HiPPO paper. See 0.2 for ODEs.

The definition of $\text{coef}_t$ above is succinct, but we can’t use it directly in an online context. That would mean constantly recomputing the coefficients from scratch. So, we take the derivative of the equation for $c_n(t)$ in 2.3:

\[\frac{d}{dt} c_n(t) = \lambda_n \int f \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} p_n^{(t)} \right) \omega_n^{(t)} \, dx + \int f \left( \lambda_n p_n^{(t)} \right) \left( \frac{\partial}{\partial t} \omega_n^{(t)} \right) dx\]We want to end up with the ODEs seen in the definitions of LegT, LagT, and LegS in 1.2-1.4. This is pretty close to what we want (remember $c(t) = (c_n(t))_{n\in[N]}$, so $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ is just the vector form), but we need to remove the partials $\frac{\partial}{\partial t} p_n^{(t)}$ and $\frac{\partial}{\partial t} \omega_n^{(t)}$.

The details of how the final expression for $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ is derived depends on what measure family you’re using, and can be found in Appendices D.1-D.3 for LegT, LagT, and LegS respectively.12 This is the part where the actual formulations of ${p_n^{(t)}(x)}_{n \in N}$ matter, and where $\lambda_n$ come into play. There’s some interesting stuff there, like how setting $\lambda_n = (2n + 1)^{\frac{1}{2}}(-1)^n$ for LegT gets you the update rule for Legendre Memory Units13, an influential preexisting RNN architecture, and you can go read the appendices if you want.

In summary, though, since we know what $p_n^{(t)}$ and $\omega_n^{(t)}$ are, we can just find their partial derivatives, plug them into the definition of $\frac{d}{dt} c_n(t)$ above, simplify, and convert summations into matrix form. Eventually we end up with the definitions given in 1.2-1.4, such as the $\frac{d}{dt}c(t) = - A c(t) + B f(t)$ form for LegT and LagT.

The ODE $\frac{d}{dt} c(t)$ would need to be discretized for use, see 0.2.14

3 Overview of HiPPO in SSMs

Relevant papers following the 2020 HiPPO papers include:

- Efficiently Modeling Long Sequences with Structured State Spaces (2021), also known as S4

- How to Train Your HiPPO: State Space Models with Generalized Orthogonal Basis Projections (2022)

- On the Parameterization and Initialization of Diagonal State Space Models (2022), also known as S4D

- Mamba: Linear-Time Sequence Modeling with Selective State Spaces (2024), also known as S6

As mentioned in 1.4, S4 used the LegS $A$ matrix for initialization, and found that it had a significant impact on the performance of the model. However, the S4 state space model is famously time-invariant (that’s what gives it its advertised property of being equivalent to a convolution) even though HiPPO LegS is time-varying. This essentially meant that S4 used HiPPO-LegS in a way that dropped the $\frac{1}{t}$ terms from $\frac{d}{dt}c(t)$ for no clear reason, and somehow it worked anyways.

Hilariously, in the follow-up paper How to Train Your HiPPO, the authors state this choice “had no mathematical interpretation” and that “it remained a mystery why this works.” The How to Train Your HiPPO paper ended up finding that the modified LegS matrix that S4 used actually corresponded to a reasonable time-invariant model, and explored some other ways that HiPPO-derived matrices could be used for initialization.

The sequel to S4, Mamba (S6), continues to use HiPPO-derived intialization. The specific matrices Mamba uses, S4D-Lin and S4D-Real, are derived in the S4D paper.

Thanks for reading!

-

The authors could have used $p_n^{(t)}(x)$ as the basis for $\mathcal{G}$ directly, but $\lambda_n$ was introduced to simplify later derivations and improve generalizability. The values of $\lambda_n$ are not important. ↩

-

https://mathworld.wolfram.com/LegendrePolynomial.html ↩

-

https://mathworld.wolfram.com/LaguerrePolynomial.html ↩

-

https://mathworld.wolfram.com/HilbertSpace.html ↩

-

There are some details about the distinction between functions and equivalence classes of functions that seem to bore even mathematicians, see: http://www.stat.yale.edu/~pollard/Courses/600.spring2018/Handouts/Hilbert.pdf ↩

-

Strictly speaking, $X = (S, \Sigma, \mu)$ for set $S$, $\sigma$-algebra $\Sigma$, and measure $\mu$, but we can treat $X$ like a set. ↩

-

A fundamental result in measure theory that allows two measures to be related in a way similar to the standard calculus definition of derivative. You’re likely familiar with probability density functions: those are Radon-Nikodym derivatives of the induced measures of random variables. ↩

-

As mentioned in 0.3, the notation is misleading here: the “$\mu^{(t)}(x)$” function that’s defined below is a density (weight) function. “$\mu^{(t)}(x)$” is the Radon-Nikodym derivative of the LegT measure with respect to the Lebesgue measure, rather than the LegT measure itself. Hence why “$\mu^{(t)}(x)$” looks like it’s defined for individual points, not subsets like a real measure. ↩

-

Again, “$\mu^{(t)}(x)$” here is a density function derived from a measure, rather than a measure. ↩

-

This section is mostly based on Appendix C. I simplified the derivations of equation 18 and 19 to remove references to tilting (in the paper, you’ll see a lot of $\chi$ and $\zeta$). Tilting allows the authors to generalize HiPPO to more bases, but is not critical for understanding the main body of the paper. ↩

-

Those are the options explored in the main body of the paper, but you could try lots of other bases if you wanted. You don’t even have to use polynomials. Fourier bases are one alternative that show up in the appendices of the 2020 HiPPO paper, and in some follow-up papers. ↩

-

Plus bonus bases, Fourier bases in D.4 and translated Chebyshev in D.5, that don’t appear in the main body of the paper. Very cool. ↩

-

https://paperswithcode.com/method/lmu ↩

-

The authors explicitly provide a discretized formulation for LegS but not the others, I assume because, being time-varying and thus having a $t$ term in its ODE, LegS is weirder to discretize. I haven’t tried discretizing any of the ODEs myself, so I’m not sure. ↩